One of the amazing games we learned about at Games for Change 2016 was Sea Hero Quest, a mobile game “where anyone can help scientists fight dementia,” a health threat that affects over 47 million people worldwide and 135 million by 2050.

Sea Hero Quest, an adventure game for iOS and Android, helps to advance scientists’ understanding of spatial navigation, which is impaired in early dementia. The game is backed by a real team of world-leading scientists, and so far it’s collected over 6,000 years’ worth of research data—just from analyzing the way people play.

We met Maxwell Scott-Slade, the game design director of the London-based Sea Hero Quest developer Glitchers, at G4C. We caught up with him by phone afterward to talk about how games like Sea Hero Quest can “crowdsource” disease research, offering a way that even students can take part—and change the way we look at key developments in science.

Sea Hero Quest helps scientists fight dementia. How does that work?

Maxwell Scott-Slade: We worked with these neuroscientists on experiments that they had done in the past [as well as] some of their colleagues in the field of human-navigational studies, and we worked backward from that to develop a gameplay concept.

Hugo Spiers at UCL [in London] had been working on real-world human navigation and adapting video games that already existed into tools for studies. Michael Hornberger from UEA [the University of East Anglia in Norfolk] was doing real-world dementia navigational studies with people in locations as well. And there are others historical experiments, like this radial maze experiment, which is about 50 years old. They used it to work out how rats would remember different [paths] down a radial maze, and the rats would get rewarded when they found the right one. All these different experiments came together to form this basis of navigational puzzles.

Hugo Spiers at UCL [in London] had been working on real-world human navigation and adapting video games that already existed into tools for studies. Michael Hornberger from UEA [the University of East Anglia in Norfolk] was doing real-world dementia navigational studies with people in locations as well. And there are others historical experiments, like this radial maze experiment, which is about 50 years old. They used it to work out how rats would remember different [paths] down a radial maze, and the rats would get rewarded when they found the right one. All these different experiments came together to form this basis of navigational puzzles.

There’s no benchmark for how humans navigate at all. The reason navigation is such a big deal is because one of the first signs of someone having dementia is that they lose their ability to navigate. So you get all these stories of people getting lost, and you hear all these things like, “Oh, they couldn’t find their way in the supermarket, and they got for hours at a time and then days, and then they were caught by police and eventually found,” and that’s usually when people start to take notice—when it gets quite severe.

All of those reasons pointed to navigation. We had all these experiments that existed in some form or another, not very game-y, very boring. Even the scientists told us, “We don’t know how you could turn this into a game, but they provide us with valuable data.” Our job was to first isolate different experiments that we thought would be possible to turn into gameplay and then try to dress them up in a way that felt like a seamless mobile game.

How does knowing how people would go through the game navigationally help with research?

Scott-Slade: I asked a very similar question when we first started because I came to this fresh just like anyone would. I didn’t know a huge amount about dementia, didn’t know about these navigational studies or how they had any relevance to the game we were making.

Really there are two kinds of navigators, broadly speaking. There are people who navigate by distal landmarks. They have an idea in their head where something is, and they’ll navigate toward that, and they’ll remember left and right turns in a way that relates to that distant landmark. It can be you might remember where a church is, and when you turn around a corner, you remember the direction that it is.

Really there are two kinds of navigators, broadly speaking. There are people who navigate by distal landmarks. They have an idea in their head where something is, and they’ll navigate toward that, and they’ll remember left and right turns in a way that relates to that distant landmark. It can be you might remember where a church is, and when you turn around a corner, you remember the direction that it is.

And then there’s another kind of navigator, and these are the people who count. They’ll count left and right turns, so if you ask for directions, some people will say, “Oh, just go toward that building, and you’ll get there.” Other people will say, “Turn left at the end of the road. Go down a couple blocks and turn right.”

[…] So the scientists basically wanted to work out on a mass scale how people navigate. Do they navigate via place learning or response learning? They’re the two styles. So their wish is, let’s have everyone in the world play the game. We’ve got about 2.5 million players. That’s a massive data set for them compared to their research studies between 50 and 150 normally. They’re very happy.

We’re splitting these people up into gender, age, location where they grew up … what kind of location it was, was it a town environment, a city environment, a countryside environment …? All these questions we drip-feed throughout the game. We’re trying to correlate different navigational styles to different attributes.

[…] The idea to the scientists is to have this huge data set so they can start to find patterns earlier and bring drug trials forward. They’ve spent about 16 billion pounds on drug trials worldwide and had no results. So they spent all this money and have not had any impact whatsoever. They think it’s because they’re getting the disease too late. So hopefully this game will create a data set that allows them to see patterns earlier and then be able to do drug trials earlier on. If they can bring it forward a decade, that would be super amazing.

Why did you choose the ocean for the game’s setting?

Scott-Slade: There was this experiment that Dr. Spiers had done where he was experimenting with paths that shifted and changed over time so you couldn’t rely on left and right navigation ability. He’d done it with lava, so he had these solidifying and melting forms of rock. And I just thought … it was kind of horrible. It felt like it was too dangerous for a game idea that was meant to be casual.

Scott-Slade: There was this experiment that Dr. Spiers had done where he was experimenting with paths that shifted and changed over time so you couldn’t rely on left and right navigation ability. He’d done it with lava, so he had these solidifying and melting forms of rock. And I just thought … it was kind of horrible. It felt like it was too dangerous for a game idea that was meant to be casual.

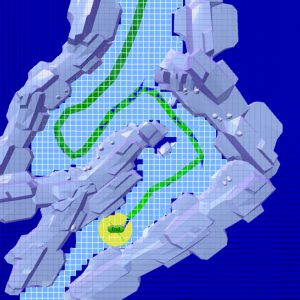

The environments had to have these kind of salient level landmarks, and that’s how recognizable something is. So you might have one tree in an environment, and that can be the navigational marker. Or you might have 20 trees, in which case they all blend into one. The Arctic felt like a really cool place, where it would have melting ice and forming ice, and it wouldn’t be weird to have bare landscapes and then landscapes that had just one tree. If you saw a few trees or a rock formation, you’d also be fine with that. It wouldn’t jolt you out of the experience.

And the ocean allows us to have thin channels, wide channels, and the motion of the boat I thought would be fun against the waves. If you’re just walking around as a player, it’s boring if the screen’s static, whereas the boat is rolling around, and there’s animation.

What was involved when you were collaborating with the scientists and researchers on developing the game?

Scott-Slade: It was really tricky to start with. First of all, it felt like everyone was trying to add every single experiment that had ever been made or done in navigational science into the game. Some of them were horrible; they’re not fun, and they could never be made fun.

The breakthrough moment was when we decided what kind of things we would open up in the game that the scientists could use as options. So we had some weather effects like fog so we could actually obscure the landscape. We had maps that could be previewed at the beginning of the level, and sometimes they’d be obscured like they were old, and you could only see what was going on a little bit. So we gave them these variables and built matrices of all the different options. And that’s how we decided there would be 45 different levels.

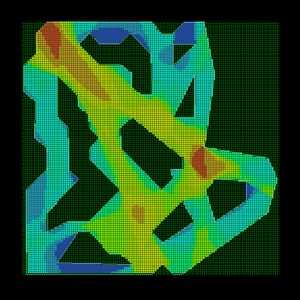

[…] I worked with a great woman who designs dementia care homes. She has a good understanding of what things people will latch onto visually and this idea of salience, that the landmarks stand out more than others, grouping landmarks, and all this stuff. So we worked with her to place landmarks in the levels, and she had this software that allowed her to put a graphic map into this algorithm, and it would create heat maps of where landmarks would be most visible. So we used that as well to make sure the levels were designed in a way that made sense from that perspective. It wasn’t just random; we worked super closely with everyone to make sure that we had a data set that was as solid as possible.

For a student learning about diseases, what are the benefits of learning about dementia and dementia research from this game than from a textbook?

Scott-Slade: The benefit of doing it this way is that it’s not forced. First of all, the game was meant to be able to be played as if it wasn’t a scientific project. As if there was no science involved at all, and there was just an hour or two with some cool-looking levels and some cool stuff to do. Obviously, it’s restricted partially by the science; it’s not the most juiced-out game you can ever imagine. It’s still a very nice experience. I think that’s important.

Dementia is one of those things … it’s not a sexy thing to talk about. It affects a lot of people, but it’s one of those things that people don’t understand at all. It’s funny, because you get so many people who play [the game], and they even think that it’s a tool that will help them know if they have dementia, like some Buzzfeed questionnaire. And it’s not like that. But I think awareness is one of the important things behind funding. Cancer is one of the biggest, most well-researched illnesses that gets a lot of attention because so many people are affected by it. But what people don’t realize is that dementia is about to overtake cancer as the biggest killer of humans. By the year 2050, it will be three times more likely. The amount of awareness versus the amount of funding it gets is unbelievable.

Dementia is one of those things … it’s not a sexy thing to talk about. It affects a lot of people, but it’s one of those things that people don’t understand at all. It’s funny, because you get so many people who play [the game], and they even think that it’s a tool that will help them know if they have dementia, like some Buzzfeed questionnaire. And it’s not like that. But I think awareness is one of the important things behind funding. Cancer is one of the biggest, most well-researched illnesses that gets a lot of attention because so many people are affected by it. But what people don’t realize is that dementia is about to overtake cancer as the biggest killer of humans. By the year 2050, it will be three times more likely. The amount of awareness versus the amount of funding it gets is unbelievable.

Sea Hero Quest is hugely an awareness tool as well as actually something that can help. Because it’s not a sexy thing, you’ll only get people who already know about it who would be interested in it. I don’t think you’ll get many teenagers going, “Oh, I’m just going to Google dementia and read up about it.”

[…] Compared with textbooks, it makes it super accessible. There’s no pressure either. You can dive in as much as you want. You can get involved in the storyline. You can just play the game sessions and not input any of your data. You can put in your data as much as you like. If you want to tell the scientists how old you are and where you grew up, it’s optional. We never made any of it mandatory. And the data is completely anonymous as well, so anyone wherever they’re playing isn’t having to submit any personally identifiable information.

There’s this idea about how if we can make the struggles of scientists more relatable to students, we can help students imagine themselves as scientists. With Sea Hero Quest, kids can take part in meaningful research.

There’s this idea about how if we can make the struggles of scientists more relatable to students, we can help students imagine themselves as scientists. With Sea Hero Quest, kids can take part in meaningful research.

Scott-Slade: Absolutely. It can bridge the gap. It can be their first experience of doing something for science. And I think for a lot of people, it is.

One of the most interesting things I didn’t know, and this is along the same lines … People who have family members who suffer from dementia, they don’t know what to do. There’s nothing they can do. Once it’s started, it’s a process that carries on until the person dies.

It was really interesting to find that a lot of people emailed in and messaged and tweeted feeling like the game, even though it was only a few minutes of their time, they felt like they could do something. That was really powerful and totally unexpected. People who are going through something intense suddenly feel like there’s something they can do. It’s a drop in the ocean, but it’s a drop in a big ocean of all these people who are having these tiny little impacts.

Is there any way that people could stay apprised of how this research is helping?

Scott-Slade: There is. So on seaheroquest.com, there is a counter of how much data [the scientists have] collected. What they’ve done is they’ve worked out how long it would take for someone to come into the lab [and] for them to go through the tests and collect this data. So they have this weird math where they’ve said, just for playing for two minutes, [this person] has contributed five hours or something. Because that’s the equivalent time for them to spend getting the same amount of data.

So they have this stat on the website that says they’ve collected over 7 millennia of scientific data, and it just keeps going up.

So they have this stat on the website that says they’ve collected over 7 millennia of scientific data, and it just keeps going up.

The scientists are getting funded for a five-year research grant, and part of that is to convert a version of the game into a screening tool so we can actually have people come into an environment where they would like to know if they have dementia and they can play a version of the game, which will then correlate their experience with a huge data set and give them an idea on a scale of where they are.

Is there anything you want teachers and students to keep in mind about this game?

Scott-Slade: It didn’t feel like it was forcing anyone to educate themselves or ramming any information down your throat. We’re doing this, and you can be part of it. It felt more like a movement, which I know is tough with some subject matter, but this is also not very sexy subject matter, either. I think it’s possible to take any subject matter and make something really clever with it with games.

Having ways we can connect what students are learning to the real world and allow them to feel like they can make a difference is really important.

Scott-Slade: That’s the whole empowerment thing, isn’t it? Like, look, you’re not just some stupid kid. You can do something. I think every kid needs that.

Gamification - Student Engagement